The Case For A Fare-Free BC

Why you should join the fight for universal fare-free public transit - even if you don't take the bus.

Universal fare-free public transit is not a new idea, but it is an idea whose day has come. A 2020 poll found that a majority of Canadians support it, and increasingly, environmental and working-class activist groups (like the Victoria Transit Riders Union, of which I am a member) are pushing for it. More and more communities are moving in this direction by expanding fare-free programs, including Montreal which abolished fares for all seniors aged 65 and up last year, and here in BC (where kids 12 and under already ride for free) the municipalities of Victoria and Kitimat have extended fare-free transit to youth aged 18 and under, and Penticton has done so up to the age of 25.

But Canada is by no means on the leading edge of this sea change. A growing list of transit systems in other countries have already abolished fares altogether, especially in Poland, France, Brazil, and the US — including those in cities as large as Kansas City and Albuquerque, New Mexico. The capital of Estonia, Tallinn, has been fare-free for residents since 2013; in 2020, the entire country of Luxembourg abolished fares completely. Meanwhile, only a few scattered small Canadian communities have been so bold. Here in BC, Summerland stands as the only municipality to abolish all fares — albeit only for its residents, and only on the lone bus route that services the community. And the province as a whole is actually moving away from fare-free: BC Transit recently invested millions of dollars into a new high-tech payment system called UMO, Translink is raising fares next month, and in here Victoria fares are also likely to increase in the near future.

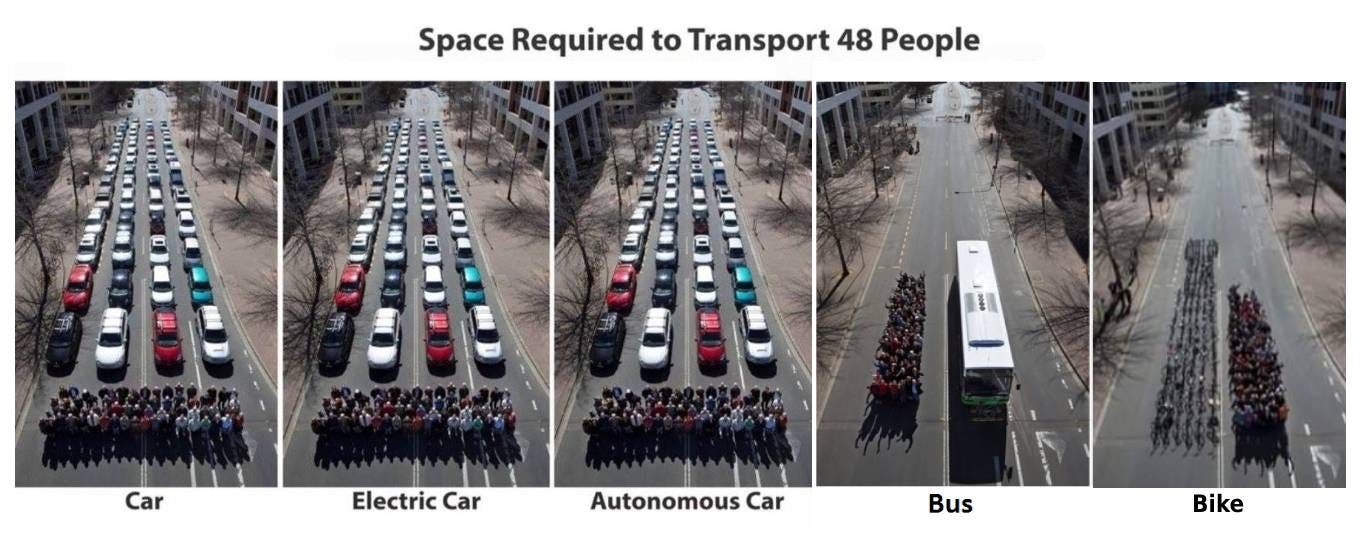

Clearly, entirely fare-free transit not only can work, but it can work at scale. So what is holding Canada back? Transit is hands down the safest and most inclusive mode of transportation, not to mention one of the healthiest and greenest after walking. It requires far less road space per traveler than does driving, potentially reducing congestion. And it is one the last remaining things us city folk do that actually brings us into personal contact with each other and thus builds community (and no, swearing at each other through a windshield does not count). Why in the world wouldn’t we abolish transit fares, which effectively disincentivize ridership?

The most obvious answer to this question is simple: cost. After all, you might be wondering, how would transit be funded if not by fares? Might not abolishing fares lead to service cuts due to funding shortfalls? Would it necessitate an increase in your taxes — something to which you might understandably object to, especially if you don’t use transit? And wouldn’t that money be better spent, for example on improving the existing quality of transit service?

I am so glad you asked.

An investment, not an expense

From the outset it should be noted that fares currently only make up a fraction of the revenue generated by BC Transit and Translink (the Metro Vancouver regional transit authority); public transit in this province has always been dependent on subsidies from Provincial and local (and sometimes Federal) government — a degree of dependence that varies regionally but which sharply increased across the board when the Covid-19 pandemic obliterated ridership.1 Indeed, Translink announced it was laying off 1,500 employees (almost 18% of its total staff), cancelling 65 routes, and reducing Skytrain service by 15-20% in the midst of the pandemic, and it only cancelled some of those plans after the provincial government promised to help cover for lost fare revenue.

From these facts, two points can be immediately made:

funding public transit entirely with public funds is not exactly a radical idea; and

fares are an unreliable source of funds ill-suited to supporting a stable and expansive transportation system, since at any moment they might decline or dry up altogether and therefore either (A) oblige transit systems to cut services, or (B) place an unbudgeted burden on government finances.

There is no Sophie’s choice between eliminating fares and improving quality of service, in other words; on the contrary, the two go hand-in-hand. Indeed, a huge proportion of the province is currently under-served — especially in rural communities —, and this is not for a lack of resources. Rather, it is a failure of the fares-based model itself. The Canadian Centre For Policy Alternatives has even stated that:

“Improving transit is not possible when systems rely on fares to operate.”

Moreover, while studies and past experience show that abolishing fares might well necessitate a net increase in public subsidy, and may even increase the total cost of operating a given transit system due to ridership increases (which history suggests would be between 30-50% but could be as high as 1000%), the subsidy per passenger significantly drops, meaning more bang per buck.2

Abolishing fares can even reduce costs and increase revenue in a number of areas. For example, no longer would infrastructure like fare boxes on busses, and turnstiles and ticket-dispensing machines at Skytrain stations have to be purchased and maintained and insured; no longer would the US company that runs the UMO and Compass Card payment systems have to be paid; no longer would armored cars have to be hired to transport the collected cash; no longer would means-testing have to be performed on applicants to low-income fare reduction programs (such that currently available to BC seniors); and so on. These fare-collecting costs are nontrivial: in fact, in smaller transit systems they may even be greater than the fare revenue they generate.

And these cost-savings stand to be complimented by the wider societal effects of fare-free transit. By enabling and encouraging healthier lifestyles and reducing loneliness and social isolation — which are widespread and have been shown to increase the risk of premature death by between 25-30% — abolishing fares could save significant tax dollars by reducing the burden on the public health system (not to mention easing the ongoing healthcare crisis).

To the degree that it facilitates a modal shift from personal vehicles to transit (more on this later), abolishing fares could also reduce road congestion, which has been estimated to cost between $500 million and $1.2 billion per year in Metro Vancouver alone. It could also reduce road maintenance costs and result in safer roads, thus reducing the cost of emergency services and traffic enforcement. And all of this is on top of the vast long-term savings associated with slowing the pace of climate change thanks to reduced carbon emissions.

In addition to savings, fare-free transit could also increase revenue by boosting tourism in the province, helping to reverse the deterioration of downtown cores, creating good union jobs, and boosting productivity. Indeed, in 2020 a study estimated that eliminating fares in Kansas City could actually increase gross domestic product (GDP) in the region by anywhere from $11.5-17.9 million (US).

From all of these points a larger observation may be derived: namely, that public transit is not an expense but an investment, and one that benefits all poor and working class people regardless of whether they ride transit or not. Car drivers stand to benefit from safer and less congested roads; those in remote rural communities stand to benefit from service expansions resulting from the substitution of the fares-based paradigm for a needs-based one; and the rest of us stand to benefit from cleaner air and a healthier, happier society. Of course we can afford to make such an investment; we can’t afford not to. If gosh darn it the money really just can’t be found, well, then I can only think of three more things to say on the subject: Tax. The. Rich.

Admittedly, funding transit is only one of the functions that fares perform. For one thing, vandalism has been observed to increase in fare-free systems, whether due to increased overall ridership, increased youth ridership, or because free products or services are perceived as being inherently less valuable and therefore less deserving of respect and appreciation than their priced equivalents. Fares are therefore often cited as a way to control vandalism.

Fares are also used to control public behavior in other ways — specifically, by reducing ridership. For example, in Vancouver travelling between zones requires a higher fare during peak travel times to discourage frivolous trips and make room for commuters. The elimination of fares would also eliminate this control mechanism, which could lead to more crowding on weekday mornings and afternoons.

Personally, I am willing to concede that vandalism and peak-time crowding might increase in a fare-free BC. But these are relatively minor considerations that are heavily outweighed by the benefits of fare-free transit, and no public policy is perfect.

What I will not concede, however, is the oft-made argument that fares have merit because they limit the transit access of certain “problem riders” — otherwise known as poor people. In fact, for reasons I will now explain, careful consideration of this argument only serves to further highlight how problematic it really is that money is charged for transit.

The “problem riders”

Will fare-free transit increase the chances that you might have to sit beside someone who is drunk or high or unwashed or having a mental health crisis? Anxieties of this sort are a major impetus of the pushback against reducing fares to zero. And to some extent this is understandable: no one like feeling unsafe or witnessing a person in distress. On the other hand, however, it is worth asking yourself whether you would be safer with this person behind the wheel of a car. If they can’t afford a car, it is further worth asking yourself whether denying them full access to transit would alleviate their distress or multiply it.

It is also worth remembering that no amount of “problem riders” will change the fact that public transit is the safest existing mode of transportation. For some perspective: in 2020 alone road accidents took the lives of 1,146 automobile drivers and passengers, 266 pedestrians, 242 motorcyclists, 50 bicyclists, and zero bus passengers across Canada. Even if you find yourself sharing a bus with the poorest person in BC you are still considerably safer than you are in a car or on a sidewalk.

Finally, it is worth critically examining the underlying assumption that the real problem riders are poor people, and therefore that fares are an appropriate way to discourage them from using transit. How strong does the correlation between problematic behavior and poverty need to be before this argument becomes more than just an exercise in prejudice and stereotyping?

In any case, despite any associated “problem riders”, the facts show that fare abolition is actually an overall safety improvement. This is certainly true for bus drivers, an overwhelming majority of assaults on whom result from fare disputes. But it is also true for passengers: in Kansas City, 80% of 1,686 people surveyed said that they felt safer on the bus as a result of that city’s Zero Fare policy.

Fare-free transit is an especially effective safety measure with regard to women, girls, and trans people, who are thus more empowered to decline rides from strangers, for example, or to avoid long walks down dark streets. It is precisely on this basis that Delhi (India) granted women the right to use its metro for free in 2019 and recently announced an extension of that right to trans people as well. Such identity-based exceptions can be stigmatizing, however, and advocates for improved women’s safety on transit in BC have instead called for fare-free transit that is universal.

Fare-free transit is also a way to improve the safety of racialized people. Adequate access to affordable transit is widely-recognized as a key Indigenous rights and safety issue — and what is more affordable than free? And fare-free transit will also take away from transit police the ability to stop people without cause for ticket checks — a power they routinely abuse to, for example, discover and report undocumented migrants to the Canadian Border Service Agency.3

Eliminating fares also enhances the safety of poor people. In fact, a 2023 experimental study found that granting low-income earners access to free transit reduced both their chances of coming into contact with the criminal justice system and their likelihood of having to visit a doctor or hospital, potentially as a result of increased activity, reduced social isolation, and therefore improved health.

Granted, this study looked at fare elimination for low-income people only, but there is every reason to think that universal fare-free transit would be even better for the health and safety of low-income people. For one thing, as with identity-based fare exceptions income-based ones can be stigmatizing. Plus, they necessitate some form of means-testing, which is never perfect and presents a significant barrier to applicants who are struggling just to survive, virtually guaranteeing that many eligible people — often those most in need — will fall through the cracks.4

(From an administrative perspective, moreover, means-testing is less efficient and incurs more expenses than does eliminating fares for all riders, further contributing to the inferiority of targeted fare-free programs relative to universal ones.)

Perhaps all of this helps explain why fare-free systems, when properly implemented, consistently meet with both support from bus drivers and dramatically increased user satisfaction.5

The safety-enhancing effects of abolishing fares extend even beyond those who use transit. Everyone is safer in a society that is more equitable, and wherein people can get to where they need to go and access whatever assistance and support they need, and in which people are healthier and happier and more accustomed to being in each other’s presence — all of which it would help effect. Conversely, disproportionately punishing poor people with transit fares, and limiting their access to essential services because they might be “problem riders”, make us all less safe, not more.

None of this should be too surprising for people who regularly use transit here in Victoria or other places that periodically offer fare-free rides, for example on Earth Day and Clean Air Day. The busses are not suddenly overrun with “problem riders” when this happens; it is more or less business as usual — maybe with the addition of a few more smiles on the faces of people who didn’t buy a monthly pass. If you are really anxious about what universal fare-free transit would look like in practice, just imagine what it would look like if every day was Earth Day and Clean Air Day.

Speaking of which, shouldn’t every day be Earth Day and Clean Air Day?

The great modal shift

Public transit is obviously a critical weapon in the existential fight against climate change and other forms of environmental degradation like ocean acidification and air pollution.6 The more people who use it instead of driving the better. According to the US Department of Transportation:

“Car transportation alone accounts for 47% of the carbon footprint of a typical American family with two cars. . . If just one driver per household switched to taking public transportation for a daily commute of 10 miles each way, this would save 4,627 pounds of carbon dioxide per household per year—equivalent to an 8.1% reduction in the annual carbon footprint of a typical American household.”

And the more crowded the bus the better, at least from an environmental perspective: a diesel bus filled to quarter capacity reduces emissions per passenger mile by 33% relative to cars; a full bus with 40 passengers on it reduces emissions by 82%. Don’t even get me started about the carbon benefits of rail-based transit.

Electric vehicles, on the other hand, are not only prohibitively expensive for many people but, among other things, also do nothing to reduce road congestion, nor to address the issue of tire dust, which is created when tires are worn down through normal use and is now thought to be the primary source of the microplastic pollution that sullies our air and oceans, and which has been detected everywhere from the Arctic to the Antarctic and from the Mariana Trench to Mount Everest.

For the sake of the planet future generations, we clearly must transition away from personal vehicles — including electric ones — and towards mass public transit (ideally in the form of trains) as the primary mode of transportation in our society. And an obvious stepping stone on this critical path is to incentivize transit use by making it fare-free: not only does this dramatically increase ridership, as previously noted, but it would also help acclimate young people to transit use and thus encourage them to make it a life-long habit.

Admittedly it is not entirely clear how effective permanently fare-free transit would be at luring BC drivers out of their cars, and many of the people who decided to take transit as a result would probably otherwise have walked or cycled or stayed at home. Studies have consistently shown that fare-free transit does reduce driving at least somewhat, but the magnitude of this so-called “modal shift” varies considerably from case to case. For example in Tallinn, Estonia universal fare-free transit has been found to have resulted in a 3% modal shift from cars to transit, whereas providing University of California, Los Angeles students with free passes yielded a 20% modal shift.

Whatever the result here in BC, the effect could surely be magnified by complimentary policies that expand and improve transit service, or which disincentivize driving (such as congestion pricing, gas tax, or pay parking) — both of which, conversely, fare elimination is conducive to, since it could both make way for a more needs-based model of service and also make the introduction of driving disincentives more politically viable.7 Moreover, even if the modal shift produced by fare elimination in BC is only 3%, in view of the planetary threat posed by climate change it is still an easy and obvious step in the right direction and, as such, well worth doing. Not to mention that this modal shift could also have a multitude of other beneficial effects, such as decreasing traffic congestion and sound and light pollution, and increasing road safety. Eventually, it could even positively effect the built environment as city planners stop catering overwhelmingly to car drivers — something that would further amplify the environmental dividends of fare-free transit, and bake them right into the landscape.

A right to the city

But the most powerful argument in favor of fare-free transit is not environmental. Nor is it about public order, quality of service, or economics. Rather, it is ethical. It goes like this: fares are an injustice, plain and simple.

In the first place, it must be said, this is because people have a right to health and safety and happiness — these are not merely side-effects of sound economic and environmental policy, or casualties of public disorder. Therefore it should be emphasized that fare-free public transit helps grant these rights to poor and working people, and that this result has merit in and of itself.

Beyond that, poor and working people also have what has been called “a right to the city”. We are the ones who built it, after all — and not just its roads and bridges and buildings, but also its communities, and its culture, and its everyday life. These are the products of our collective labor, both paid and unpaid: we produce them when we build something, but also when we visit friends, take care of a loved one, walk a dog, go shopping, cook, or garden. It is a grave injustice that capitalism has usurped the fruit of this labor, commodified it, profited from it, and turned it into an instrument of our oppression; winning the fight for basic freedom of movement is an important step towards correcting this injustice, democratizing everyday life, and reclaiming ownership of the cities that we have built.

Armed with this concept of the right to the city, the fight for fare-free transit can be understood as being about much more than the cost of bus fare. It is also about de-commodifying public transit and re-conceptualizing it as a public good akin to public libraries and public parks. It is about pushing back against the capitalist class (the bosses and the landlords and the financiers) who have alienated us from everyday life and in doing so debased our very existence. And it is central to the larger struggle of poor and working people to reclaim our right to collective self-determination — to make and remake our collective selves by making and remaking our cities — a right that the Marxist geographer David Harvey calls:

“one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights.”

After all, the environment in which we reside to a large extent determines who we are, and in particular who we are as an aggregated whole. Poor and working people should have the right to shape this collective identity as they see fit, not to have it dictated to them.

Of course, winning fare-free transit alone will not reclaim this right, which in Harvey’s words necessitates “command [of] the whole urban process”; freedom of movement is clearly necessary but not equivalent to this. Thus, the right to the city framework also serves to highlight the important point that eliminating transit fares is only one battle — albeit a critical one — in a larger class war.

In fact, victory in this battle will be Pyrrhic if we do not fight on. The capitalists can be fully expected to counter-attack, to attempt to implement fare-free transit in such a way that it is designed to fail, or to try and position themselves as its primary beneficiaries at our expense. We must therefore be prepared to defend against this — and to keep advancing, for example to institute land value capture mechanisms to prevent the public money invested in fare-free transit (not to mention libraries, hospitals, parks, roads, streetlights, and so on) from driving up the value of nearby land to the enrichment of private interests and the detriment of renters. And we must also fight to secure further investment in expanding transit services (including intercity services, particularly in the vast transit deserts in northern and interior BC), and to put the most qualified people (i.e., transit workers and unions) in charge of this expansion.

In other words, the fight for universal fare-free transit is necessarily part of a larger, revolutionary push for the human rights of poor and working people. And that brings me to the final reason why you should join this fight (even if you don’t use transit): namely, the relatively favorable terrain on which to open this larger campaign.

The journey is the destination

As I said in the introduction, universal fare-free transit is an idea whose day has come. And I honestly believe that it is just a matter of time before it becomes a reality in BC: for all the reasons I have laid out, it just makes too much sense. This is not to say that we don’t have to fight for it — we do —, nor that it will be an easy fight — it won’t be. But as a popular policy that can appeal to poor and working people across the political spectrum, and which stands to boost the appeal of politicians who endorse it, it is a low-hanging fruit relative to other major milestones on the road to defeating climate change and capitalist oppression. And this makes campaigns for a fare-free BC promising as recruitment vehicles to capture the imaginations of poor and working people, organize them, and bring them into the larger fight against capitalism. The fight for fare-free transit is not just a means to an end, therefore, but also an end unto itself.

Victory in this fight, moreover, could have an immediate, tangible, positive effect in many BC residents’ lives and could thus act as a constant, inspiring reminder that we when we fight we can win, and that winning makes the fight worthwhile. And success in BC could set a shining example for the rest of the country to follow.

Thus, campaigns for a fare-free BC are promising as catalysts for even larger, potentially nation-wide societal changes — a potential that sets them apart from other transit-related campaigns, like those calling for the creation of bus-only lanes. For dramatic illustration: protests against transit fare hikes in Santiago, Chile in 2019 eventually gave rise to a national movement that swept Gabriel Boric into the president’s office and very nearly led to a much-needed progressive re-writing of Chile’s Pinochet-era constitution.

Obviously BC and Chile are very different, and jumping straight into a fare strike here would probably have relatively little impact. (Does anyone remember the one that the Vancouver Bus Riders Union called in 2004?) Instead, it seems more practical to start by pushing for expanded fare-free programs such as already exist for youth and seniors (the Victoria Transit Riders Union is still new, but already we have had some success finding municipal government support for expanded, province-wide youth and seniors fare-free programs). If won, the success of these expanded programs — as has already been seen in Montreal — can then be used to argue that fare exemptions should be expanded still further, as can the relative absurdity of obliging only those of working age to pay, regardless of their income or employment status. And even if it is not won, the public conversation and increased awareness generated by such tactics can still be built upon so that, eventually, an effective fare strike might become feasible.

This is hardly a comprehensive campaign playbook, but hopefully it nonetheless makes clear that a feasible road to a fare-free BC exists if only people like you would get on board. So what are you waiting for? Click here to get in touch with the Victoria Transit Riders Union (or, if you don’t live in BC, reach out to another, more local group like Free Transit Toronto, Free Transit Ottawa, or Free Transit Edmonton), or start your own, similar group. Together, we can get this train moving. Next stop: free and excellent transit for all.

As far as I can tell, even in high farebox recovery areas like Vancouver and Victoria fares only pay for about 50% of the operational costs of transit — a number that is likely substantially lower in smaller communities.

The widely-cited Simpson–Curtin elasticity model suggests that you can increase transit ridership by 1% for every 3% reduction in fares, but reducing fares by 100% seems to defy this model.

Apparently Vancouver Transit Police reported 328 undocumented people to the Canadian Border Services Agency in 2013 alone.

Means tests are commonly based on tax returns, which can fail to account for recent declines in an applicant’s financial fortunes, and which automatically disqualifies anyone who is not up-to-date with their tax filings — as is common among low-income people.

Bus driver’s support for abolishing fares could stem from the fact that, in addition to making them safer, it also increases operational efficiency by streamlining their jobs, allowing them to focus on driving and interacting positively with the public, and speeding per-person bus boarding times by allowing people to enter through both the front and back doors.

Air pollution not only traps heat, it should be noted, but it also kills a lot of people. In fact, according to the World Health Organization “one third of deaths from stroke, lung cancer and heart disease are due to air pollution”.

Some researchers have suggested that service improvements are more a effective use of resources than fare elimination in terms of facilitating a car-to-transit modal shift, but this is premised on the false presumption that these two things are mutually exclusive, when, as we have seen, they actually go hand-in-hand.