Evidence suggests that the Afghan War may have been a major cause of the toxic drug crisis currently devastating Canadian communities. By virtue of its participation in this war, therefore, the Canadian military is implicated in this public health crisis.

Toxic drugs have consumed well over 30,000 lives in Canada in the last seven years alone. For comparison, a total of 158 members of the Canadian Armed Forces were killed in the course of Canada’s fourteen-year-long involvement in the Afghan War.

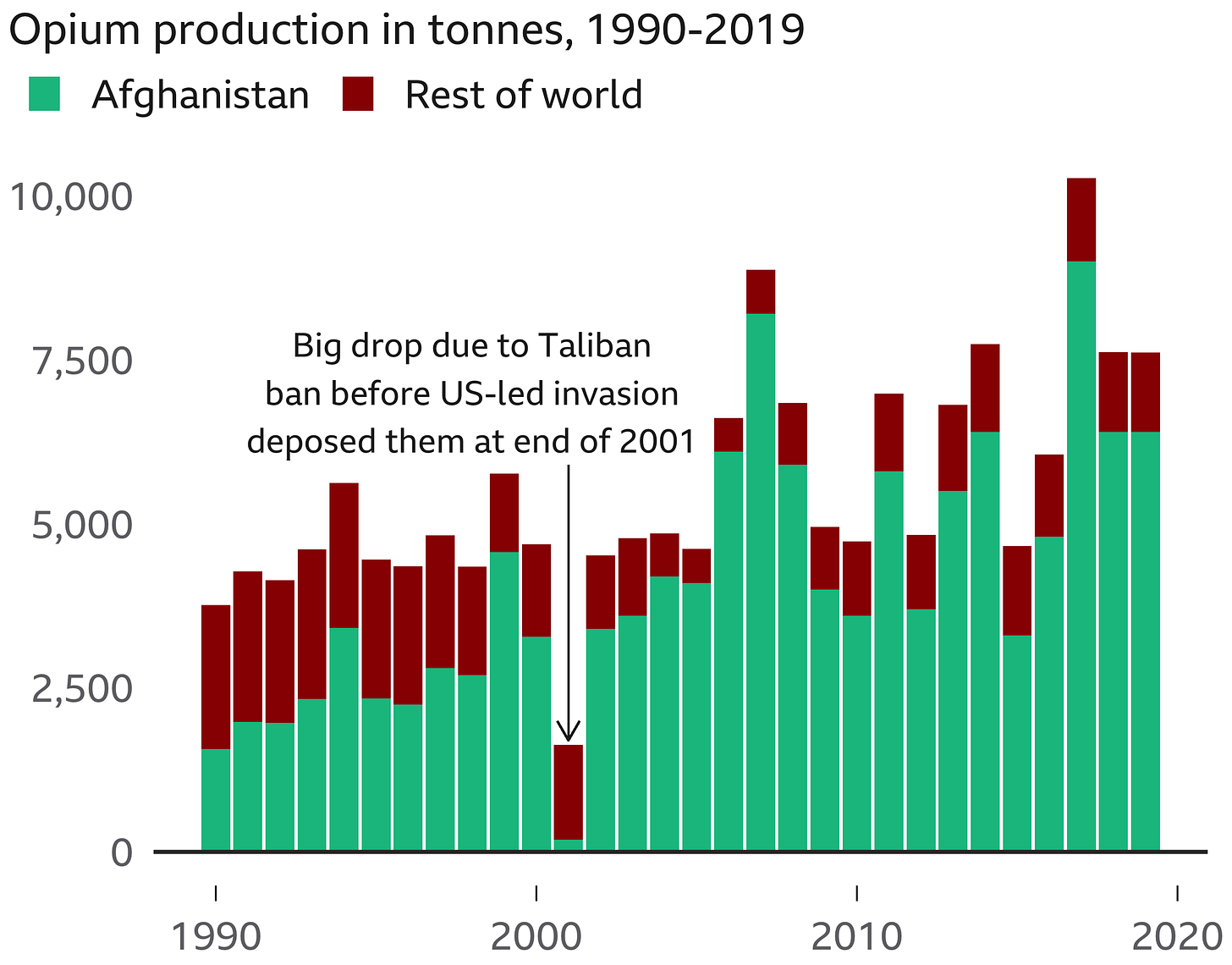

Links between this war and the Canadian toxic drug crisis are far from obscure, although they have been largely ignored by the media. It is, for example, well-known that occupied Afghanistan was — by far — the world’s leading producer of opium.

Somewhat less well-appreciated is that the invasion and occupation itself appears to bear responsibility for this. As a measure of this responsibility: opium production soared to unprecedented heights in occupied Afghanistan such that the country produced between 80-90% of the global supply. Moreover, the occupation was bookended by the near-total elimination of opium production in the country due to bans imposed (for practical and moral reasons) by the Taliban: first in 2001, just prior to the US-led invasion, and again in 2022 after the American withdrawal. This latest ban has recently been credited for reducing opium production in Afghanistan by a full 95%.

Considering these facts, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the occupation itself was responsible – whether directly or indirectly – for the massive amounts of opium produced in Afghanistan between 2001-2022. And this clearly implicates the Canadian military, which was an occupying power in Afghanistan from 2001-2014.

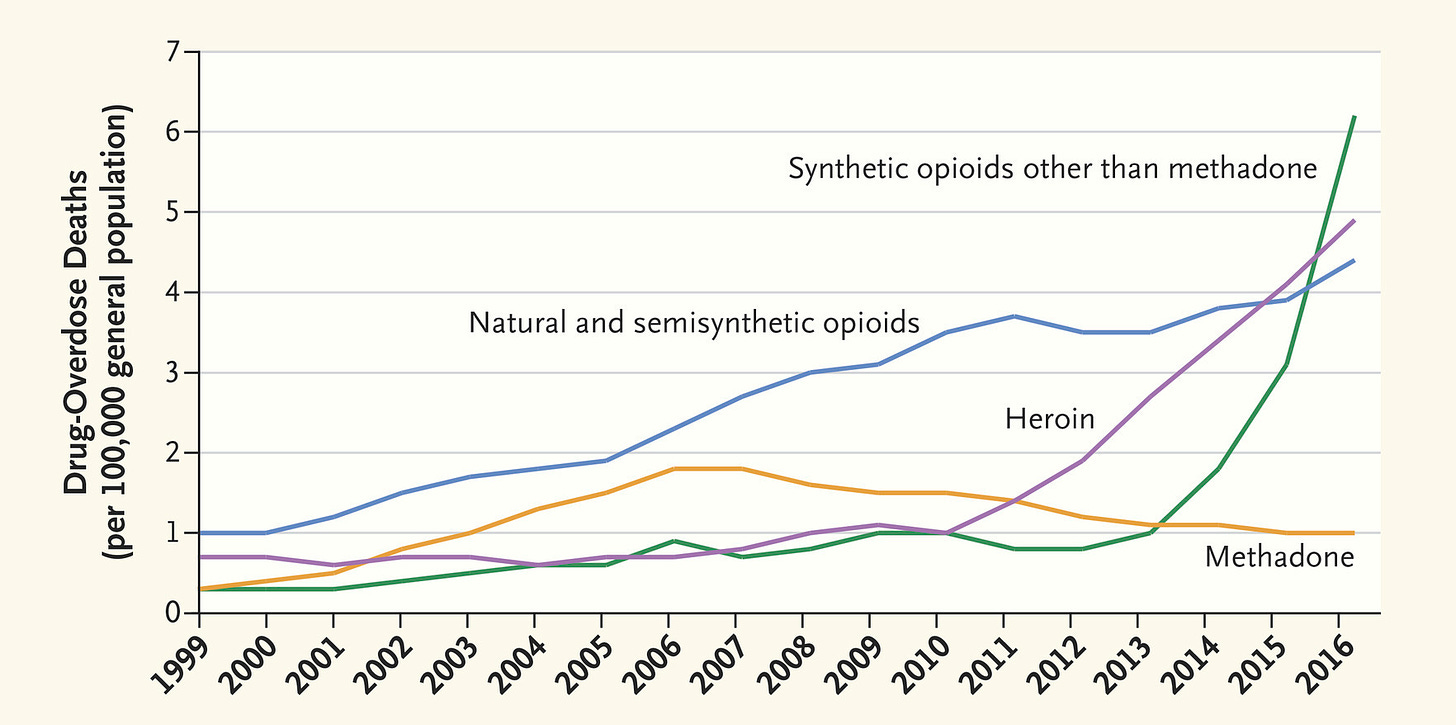

The connection between the post-invasion boom in Afghan opium production and the subsequent epidemic of opioid use in Canada – which then translated into the devastating toxic drug crisis – is admittedly not entirely straightforward, but it is certainly sufficiently obvious that it is reasonable to expect it to have garnered far more media attention than it has to date. For example, there is a clear temporal correlation between the Afghan War and the dramatic rise in opioid overdose deaths in North America.

Despite this correlation, however, the Canadian media have almost universally dismissed the war as a causal factor in the opioid epidemic. The basis for this dismissiveness is twofold. First, the media have uncritically accepted the official claim that Afghan opium and heroin overwhelmingly “ends up in Europe and the US” but that Canada somehow does not receive it in significant quantities. Second, while the media have rightly focused on the role that prescription opioids like OxyContin played in the opioid epidemic, they have, for whatever reason, overlooked connections between these legal prescription opioids and the illegal opium and heroin that gushed out of occupied Afghanistan.

But both of these predicates fall apart upon closer inspection. As to the claim that occupied Afghanistan did not supply the Canadian black market: in fact, no one really knows where illegal drugs end up, as should become obvious with a moment’s reflection. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has underscored this fact, writing in 2009 that:

“North America consumes around 20 tons of heroin every year. Since Latin America reportedly produces less than this amount, either several tons of heroin are being trafficked from Afghanistan, or Latin America produces more heroin than reported.”

It is also noteworthy that the US, which is also in the throes of a toxic drug crisis, likewise officially claims that occupied Afghanistan accounts for “only a small portion of the US supply”.

But foreign media sources tell a different story: just as Canadian media have pointed to the US as a major destination for heroin from occupied Afghanistan, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) reported in 2019 that 90% of Canada’s heroin came from Afghanistan.

What’s more, when the Taliban outlawed opium production in 2001, strange “heroin shortages” were reported in both Canada and Australia. And when an investigation into the causes of these shortages was published in the peer-reviewed journal Addiction in 2006, it concluded that these shortages could have been caused by the Taliban’s 2001 move against opium production in Afghanistan. The authors tactfully added that:

“Because the Taliban’s opium ban could explain the apparent Canadian ‘heroin shortage’, it is notable that Canadian enforcement experts have concluded that Canada also does not receive measurable quantities of heroin from Afghanistan. Both Australia and Canada are purported to obtain the vast majority of their heroin from Myanmar.”

What the authors did not make explicit is that both Canada and Australia were occupying powers in Afghanistan at the time this study was published, making the admission that Afghanistan was indeed a major supplier of illegal opioids to their respective domestic markets embarrassing to say the least.

The second basis for the Canadian media’s oversight of the connection between the Afghan War and the domestic toxic drug crisis – namely, that the opioid epidemic was sparked by legal prescription drugs that were not produced by occupied Afghanistan nor sourced from Afghan opium – is also vulnerable to scrutiny. Primarily, this is because the production of both legal and illegal opium affects the global price of opium, and the global price of opium, in turn, affects the trade of both legal and illegal opium. This effectively blurs the line between legal and illegal opium even assuming that illegally-sourced opium does not surreptitiously enter the legal market.

A remarkable study conducted in 2019 by a team of economists at Essex University illustrates this point. This remarkable study, which focused on the opioid epidemic in the US but which is clearly applicable to Canada, demonstrates just how blurry the line is between “legal” and “illegal” opium. Although the authors “do not claim that pharmaceutical companies make use of raw opium sourced illicitly”, they nonetheless show that:

“the quantity of [opioid] drugs prescribed in the US [is] positively related to changes in the production of opium in Afghanistan”.

Furthermore, the study demonstrates that this correlation is no coincidence but rather a straight-forward function of the profit incentive. Simply put, it is cheaper to make opium-containing drugs (like Oxycontin) when the price of opium is low, which, in turn, leads to greater profits. And because Afghanistan produces the vast majority of the world’s opium, the authors write:

“opium price changes in Afghanistan are associated with changes in the expected future profits of the pharmaceutical companies that produce opioid-based drugs, and hence with the economic incentive to promote and sell them.”

Unsurprisingly, therefore, the study finds that there is a correlation between the price of opium in Afghanistan and the aggressiveness with which prescription opioids are marketed in the US. This is of particular note because the overly-aggressive marketing of prescription opioids is widely seen as the primary cause of the modern opioid crisis in both the US and Canada. Numerous successful lawsuits launched against prescription opioid producers and distributors like Purdue Pharma, Johnson & Johnson, Walgreens, and Walmart (to name just a few) have all but proven that they enthusiastically pushed opioids on doctors and patients, and downplayed the risk of addiction, in their reckless pursuit of profits.

In fact, although the opioid epidemic only came to the general public’s attention around 2009, the study finds that the stock market was already accurately predicting that increased opioid prescriptions would result from lower opium prices well before that. This, as the authors note, suggests that “investors expect opioid manufacturers to exploit opium price fluctuations”, and that they invest accordingly.

To poor and working people, on the other hand, who tend not to own stocks, and who are most at risk of death from an opioid overdose or drug poisoning, the study’s conclusion that the opioid crisis has its genesis in the decades-long occupation of Afghanistan may well come as a surprise — even now, in 2023.

All of this suggests that Canadian society has been scarred far more deeply by the Afghan War than is generally recognized: indeed, it suggests that huge numbers of Canadian citizens may have lost their lives, or their loved ones, as an indirect result of the 2001 invasion and occupation – not to mention the innumerable Canadian citizens who have suffered grievous injuries that often result from drug poisoning.

In economic terms, the toxic drug crisis has been estimated to cost Canada $5.71 billion annually, which is roughly a fifth of the country’s entire defense budget. And unlike the Afghan War, from which Canada withdrew in 2014, the toxic drug crisis has only continued to grow with no end in sight, consuming tax dollars that might otherwise have been spent addressing the healthcare crisis, or the housing crisis, or on providing affordable education to Canadian citizens.

This blowback is not, of course, the fault of individual soldiers. Many soldiers, including many of those who served in Afghanistan, have themselves become victims of the the toxic drug crisis: in fact, a 2019 study of US veterans of the Afghan War (entitled “Did the war on terror ignite an opioid epidemic?”) found:

“consistent evidence that combat assignment substantially increases the risks of prescription painkiller abuse and illicit heroin use.”

And a more recent analysis has shown that overdose deaths among US veterans increased by 53% between 2010-2019, taking the lives of 42,627 veterans over these nine years. This dwarfs the 2,402 combat deaths that the US suffered during the whole 21-year-long Afghan War.

And although it can be safely assumed that the Canadian veteran population has also endured similarly elevated rates of overdose, this data does appear to be readily available. In fact, the Canadian military does not even seem to be monitoring the problem. “Lest we forget”, indeed.

Rather, evidence linking the Afghan War to the opioid epidemic that transformed into the ongoing toxic drug crisis implicates the Canadian military as an institution, as well as the capitalist system it serves. Individual soldiers are themselves victims of these structures, just as are civilians.

Furthermore, this evidence suggests that the full cost of the war has yet to be recognized by the general public, thanks in large part to the self-interested lies and omissions of the Canadian military, government, and media – the same institutions that are falling over themselves today to glorify military service and profess the utmost respect for those who enter into it. (In fact, when I first wrote about this link two years ago, the only other similar story I could find online had been publish by a site called South Front, which has since faced Western censorship as a wellspring of “Russian disinformation”.)

Evidence linking the Afghan War and the opioid epidemic also brings new meaning to Remembrance Day, which is commemorated in Canada every November 11th (today) and is symbolized, ironically, by the poppy: the same plant that provides the raw material from which opium is refined.

The reasons for these lies and omissions are well worth reflecting on this Remembrance Day weekend. There is no national day of remembrance dedicated to the victims of opioids, after all; just a long moment of silence.

How The Canadian Military Helped Fuel The Toxic Drug Crisis That Has Killed Tens Of Thousands Of Canadians (Audio Version!)